Scientists’ drilling mission on remote and inaccessible glacier

A team of researchers from the UK and Korea has reached the most inaccessible and least-understood part of Thwaites Glacier in West Antarctica where they will drill through the glacier to directly observe how warm ocean water is melting it from below.

Researchers from British Antarctic Survey (BAS) and the Korea Polar Research Institute (KOPRI) have arrived at Thwaites Glacier in West Antarctica, one of the largest and fastest changing glaciers in the world. Thwaites Glacier – which is around the size of Great Britain or the US state of Florida – has been nicknamed the Doomsday Glacier. With ice up to 2,000 metres thick in places, if the glacier were to collapse, global sea levels would rise by 65cm.

Despite the importance of Thwaites, little is known about the ocean processes that drive melting from below the ice. This is especially true for the ice shelf seaward of the fastest flowing part of Thwaites Glacier. Over the next two weeks, the team will use a hot water drill to bore through the ice and deploy instruments that will send back the first real-time data from this critical location.

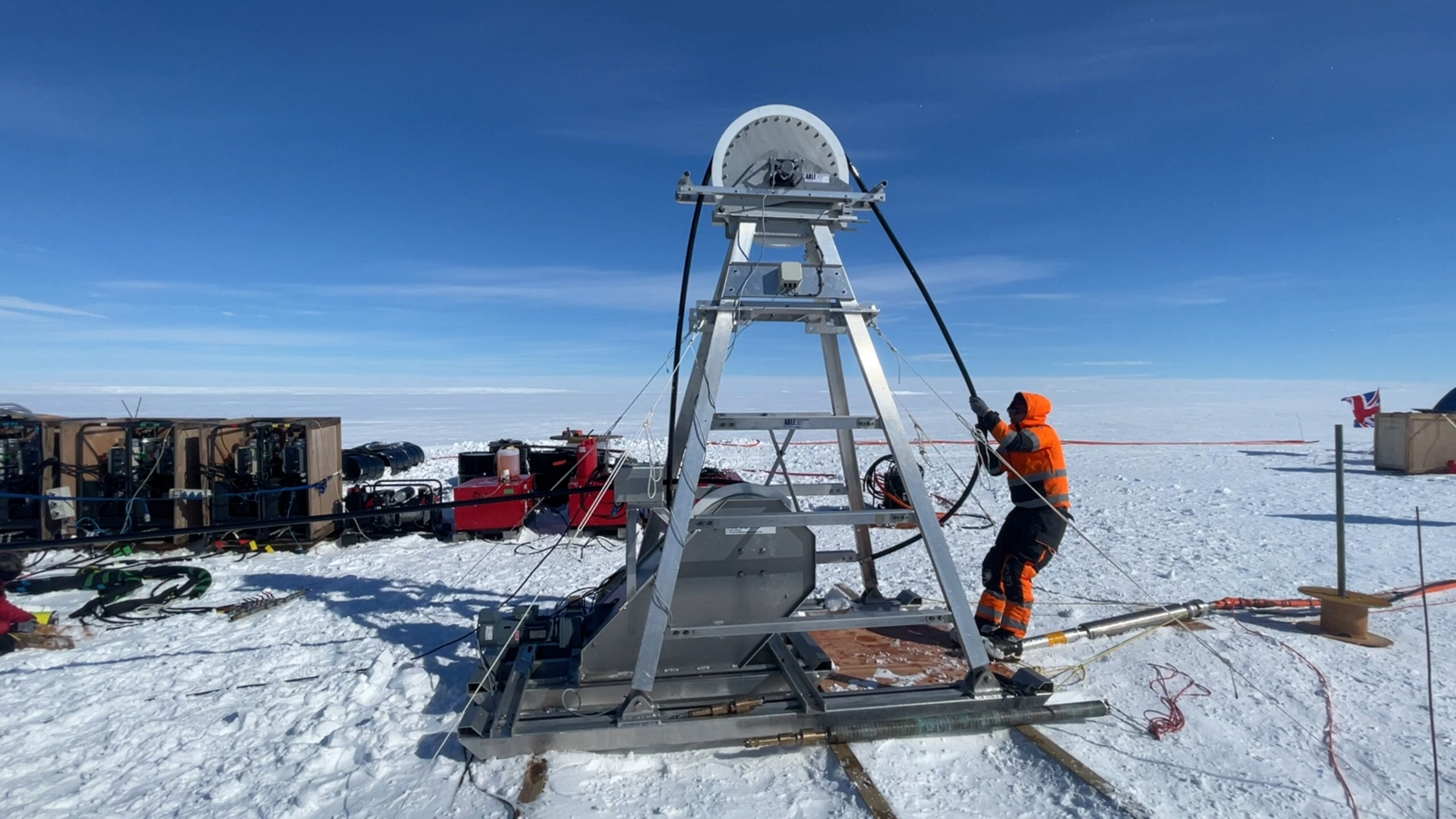

This is the first time hot water drilling has taken place on the main trunk of the Thwaites ice shelf. The area is heavily crevassed and fast moving, making research here incredibly challenging.

The team will drill 1000m through the ice, just downstream of the grounding line – the point where the glacier lifts off the seabed to become a floating ice shelf. This is Thwaites’ most vulnerable point, where the warmest ocean water flows under the glacier and melts it from below.

Once complete, they will lower instruments through the hole to collect the first long-term direct measurements of ocean temperature and currents at this location. The researchers will also collect sediment samples and water samples to learn more about what happened at Thwaites Glacier in the past, and what’s happening now.

Dr Peter Davis is a physical oceanographer at British Antarctic Survey. He said:

“This is one of the most important and unstable glaciers on the planet, and we are finally able to see what is happening where it matters most.

This is an extremely challenging mission. For the first time we’ll get data back each day from beneath the ice shelf near the grounding line. We’ll be watching, in near real time, what warm ocean water is doing to the ice 1,000 metres below the surface. This has only recently become possible – and it’s critical for understanding how fast sea levels could rise”

The team has two weeks to complete drilling. Once the instruments are in place, they will send data each day for at least one year via Iridium satellites, providing scientists with a never-seen-before look into the processes driving change at one of Earth’s most important glaciers.

The Korean-led two-month expedition saw the team sail from New Zealand aboard RV Araon, the Korean icebreaker ship. After three weeks at sea, they arrived at Thwaites Glacier, where they waited for a weather window to fly helicopters onto the ice.

Dr Won Sang Lee, a principal research scientist at the Korea Polar Research Institute and leader of the expedition says:

“This is polar science in the extreme. We made this epic journey with no guarantee we’d even be able to make it onto the ice, so to be on the glacier and getting ready to deploy these instruments is testament to the skills and expertise of everyone involved from KOPRI and BAS.”

Before the team and equipment could be taken to the ice, an experienced field team used a remote-controlled vehicle to tow a ground-penetrating radar to scan for hidden crevasses beneath the surface. Once a safe location was established, the drill team completed the 18-mile flight to the drill site. Over 40 helicopter rotations were required to transport the 25 tons of equipment the team will need to live and work over the next two weeks.

Half a century of drilling expertise

BAS is a world leader in hot water drilling. Over more than five decades, BAS researchers and engineers have developed the technology and expertise to drill through ice more than 2,000 metres thick.

The technique involves heating water to approximately 90ºC and pumping it at high pressure through a hose to melt the ice. This creates a roughly 30cm diameter hole, with the hot water melting up to 1 metre of ice each minute. Once drilled, the holes refreeze within one or two days, so the drill is used periodically to keep them open.

Dr Keith Makinson is an oceanographer and drilling engineer at British Antarctic Survey. He said:

“We’re world-leaders in this technology – between us, this team has about 75 years’ worth of hot water drilling experience. Over the past four decades it’s been amazing to see this technology develop, and now it’s helping to answering crucial questions about how we’re all going to be affected by climate change and rising sea levels.”

Drilling through the ice allows scientists to collect data about the ocean and seabed beneath floating ice shelves, and the bedrock under grounded ice. This information is vital for understanding how glaciers like Thwaites are contributing to sea level rise.

The Doomsday Glacier

Between 2018 and 2024, an international research team led by the UK and US (the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration) has studied the glacier to understand how far and how fast this unstable glacier will melt as the climate warms. Their research focused on more stable areas of the glacier. Until now, the main trunk of Thwaites has remained largely unexplored due to its crevassed and dynamic nature.

Understanding how Thwaites Glacier behaves is critical for predicting future sea level rise. Millions of people in the UK live in coastal communities, and rising seas threaten cities, infrastructure sand livelihoods around the world. The data collected on this expedition will help scientists improve predictions of how quickly sea levels could rise, giving governments and communities more time to plan and adapt.