The big breakup: why do scientists love enormous icebergs?

Who doesn’t love a giant iceberg? There’s something deeply compelling about these frozen monsters that tear free from Antarctica’s coastline and wander across the Southern Ocean. News editors know it well: a story about a colossal berg almost always lands with readers.

It’s no different at the British Antarctic Survey (BAS). Whenever our scientists talk about icebergs in public, audiences are captivated. Flat-topped blocks of ice the size of cities — sometimes far larger — spark a childlike sense of wonder. And in recent years, there’s been plenty to marvel at. Since 2020, at least five icebergs bigger than 1,000 square kilometres have drifted across our screens, each one large enough to dwarf the Isle of Wight.

Yet these dramatic breakaways are far more than photo opportunities for passing cruise ships. They are now objects of intense scientific interest, offering fresh clues about the polar environment today, and deep into Earth’s past.

The crumbling edge of A23a, from first in-person drone observations in December 2023 made by the team on board RRS Sir David Attenborough (Credit: British Antarctic Survey)

The birthplace of giants

Each year, Antarctica sheds a staggering volume of ice into the ocean: roughly 1,000 billion tonnes calve away to form new icebergs. That’s about 1.1 trillion cubic metres of ice: enough to fill around 270,000 Wembley Stadiums every year, or almost one full stadium every two minutes.

Satellites typically track upwards of 100 major calving events (larger than one square kilometre) annually. But the true number of smaller bergs, the so-called “bergy bits” and “growlers”, is likely in the many thousands, and possibly millions.

Understanding what triggers these breakaways is the focus of a BAS project called RIFT-TIP, or Rates of Ice Fracture and the Timing of Tabular Iceberg Production. Researchers are studying how cracks, or rifts, grow and link together until a block finally detaches. This is work taking place on the Brunt Ice Shelf, which released three major bergs (A81, A74 and A83) earlier this decade. Sensors have been embedded in the ice, and samples are being crushed in the lab to reveal how frozen water behaves under stress.

Project leader Dr Oli Marsh says the aim is to build more realistic physics into computer models, so scientists can better recreate, and anticipate, calving events. Researchers are getting increasingly good at predicting where a major crack will travel across an ice shelf. But pinpointing when it will finally snap remains fiendishly difficult. The process is non-linear.

“As little as a few kilopascals of stress can shift the timing by decades,” Oli explains. “It either happens – or it doesn’t.”

Icebergs can reach genuinely mind-boggling scales. The largest ever measured was B15, which calved from the Ross Ice Shelf in 2000. It originally spanned 11,000 square kilometres, and a sizeable fragment is still being tracked 25 years later.

History buffs sometimes cite a 1956 report from a US Navy icebreaker that claimed to have seen an even larger object. But without satellites, modern scientists remain sceptical. BAS collaborator Dr Ted Scambos, from the University of Colorado has investigated the account.

“The claimed size is extraordinary — about 335 by 97 kilometres, more than three times B15,” he says. “Our best guess is that observers from an aircraft likely combined one large iceberg, or several, with a wide expanse of ‘trapped’ sea-ice around it.”

The power of calving

Scientists are also learning that the impact of an iceberg begins the very moment it breaks free. When a grounded glacier calves, it can generate so-called “internal tsunamis”. As ice plunges from a cliff face and rolls into the sea, it sends powerful underwater waves rippling through the ocean.

BAS polar oceanographer, Professor Mike Meredith, says these events release astonishing amounts of energy.

“When marine-terminating glaciers calve, potential energy is suddenly unleashed — from ice falling under gravity and rising through buoyancy,” he explains.

These internal waves can mix the ocean more powerfully than winds or tides, drawing up heat and nutrients while also pushing carbon down to depth. In one case, Mike’s team estimated that a one-kilometre-wide collapse from the front of William Glacier in the Antarctic Peninsula injected up to 2.4 terajoules of energy into the surrounding water — broadly comparable to the energy needed to bring 2.5 Olympic swimming pools to the boil.

BAS now runs a dedicated programme, POLOMINTS (Polar Ocean Mixing by Internal Tsunamis), to study this process.

Next stop: nutrient city

As icebergs drift north and melt, they don’t simply disappear — they reshape the ocean around them. Icebergs carry mineral-rich dust and rock scraped up from the continent when they were still part of a glacier. By releasing that material at sea as they melt, the bergs can act as both fertiliser and oasis for marine life.

“Icebergs give the ocean a double whammy,” says BAS ecologist Professor Geraint Tarling. “Their meltwater releases nutrients, while their deep keels churn up even more from layers that rarely reach the surface.”

The Southern Ocean isn’t short of big nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus. What it lacks are trace metals, especially iron and manganese, which icebergs supply in abundance. When they melt, they can trigger vast phytoplankton blooms. Where microscopic algae thrive, so too does krill — the tiny crustaceans that underpin the Antarctic food web, feeding whales, seals, penguins and other seabirds. Around big bergs, feeding frenzies are common.

This productivity also links directly to climate change. Phytoplankton absorb sunlight, nutrients and carbon dioxide to grow. When they die, much of that carbon sinks to the seafloor, effectively locking it away. BAS biogeochemist Dr Laura Taylor says this raises a crucial question:

“If giant icebergs become more frequent as the climate warms, will they amplify that warming — or act as a brake by helping store more carbon in the deep ocean?”

Orca in front of A23a (Credit: Liam O’Brien)

Up Iceberg Alley

The freshwater released by melting icebergs is immense. At the peak of its decay in late 2020 and early 2021, the giant iceberg A68a was dumping more than 1.5 billion tonnes of fresh water into the ocean every single day – over 150 times the daily water use of the entire UK population.

Much of this activity occurs along “Iceberg Alley”, a busy corridor of drifting ice that runs from the Weddell Sea towards South Georgia. Far from being just a graveyard for ice, this region is a geological archive. When icebergs melt, much of that ice-rafted debris mentioned above will sink and become embedded in seafloor mud. By drilling into these sediments, scientists can read a record of past iceberg traffic millions of years into the past.

BAS marine geologist Dr Claus-Dieter Hillenbrand explains that chemical “fingerprints” in the grains can reveal where bergs came from.

“Sometimes the signal points broadly to West Antarctica. In other cases, we can narrow it to the northern Antarctic Peninsula, the western Amundsen Sea — or even a specific rock outcrop.”

These records shed light on the mid-Pliocene warm period, around three million years ago — a time when atmospheric CO₂ was roughly 400 parts per million, similar to today.

Perhaps surprisingly, the sediment evidence suggests far fewer icebergs passed through Iceberg Alley back then than now. That makes sense if Antarctica’s ice sheet was significantly smaller, as other evidence also suggests. With fewer glaciers reaching the sea, there were fewer opportunities to calve icebergs. Today’s more extensive marine ice sheet, by contrast, acts like a far more efficient “iceberg factory”.

Headlines about another recent behemoth, A23a — at nearly 4,000 square kilometres, for a while the world’s largest iceberg — have fuelled speculation that we may even be in the midst of a sudden surge in major calvings.

But the data doesn’t support this idea. Dr Mickey MacKie at the University of Florida analysed satellite records back to the late 1970s and found no clear upward trend in the size of the largest annual icebergs.

“Really big icebergs may actually signal stability, not instability,” she suggests. Large bergs often come from ice shelves that calve in natural cycles over decades.

By contrast, when ice shelves collapse, they usually shatter into many smaller pieces — a process she calls “death by a thousand cuts”.

The challenge of tracking

Whether big or small, tracking icebergs is vital for both science and safety at sea. BAS remote-sensing expert Dr Andrew Fleming says that while satellites can easily spot city-sized bergs, it’s the smaller ones that endanger ships.

“The real risk is the ice you can barely see – fragments that lurk just below the surface. Hit one at speed, and you’re in serious trouble.”

Andrew is working towards an automated Antarctic iceberg monitoring system using satellite data. For those smaller bergs, this would map likely ice density rather than individual blocks, helping vessels avoid hazardous waters. The system would be modelled on one that already operates around Greenland.

He’s also working with the AI Lab at British Antarctic Survey, who are developing AI tools to reconstruct the “family tree” of icebergs – tracing which fragments once belonged together. This could improve both navigation forecasts and scientists’ understanding of how and where Antarctica is losing mass.

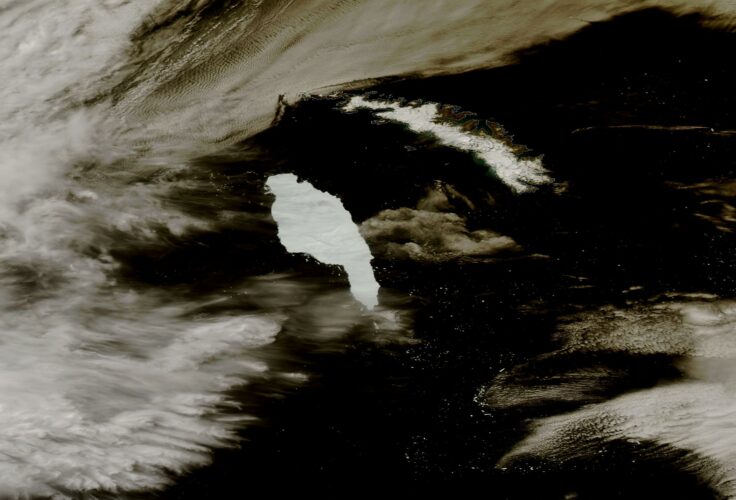

A68 near South Georgia on 14 December 2020 – Credit: NASA MODIS (Worldview snapshot)

Finally, there’s a lively debate developing over how icebergs are named. At present, they are labelled for the sector of the Antarctic where they are first seen (A, B, C or D) followed by a number, with letter suffixes added as they fragment (A68a, A68b, A68c). The system, run by the US National Ice Center, is efficient — but hardly inspiring.

Some scientists argue that giving icebergs real names, like storms, could help the public connect more deeply with polar science and climate change. Would you feel differently about Iceberg Mike or Iceberg Amy than about D15a? It’s a simple idea, but one that could change how we talk about a rapidly changing continent.