How do we actually know Antarctica is melting? Mass balance explained

30 July, 2025 Beyond the Ice

When news broke that Antarctica had gained ice mass between 2021 and 2023, it sparked debate across comment sections worldwide. How could the continent be gaining ice when we’re constantly told it’s melting? The reality reveals fascinating insights into how Antarctica’s ice system responds to extreme weather.

Climate scientist Dr Michelle Maclennan from British Antarctic Survey explains how scientists measure ice changes across this enormous continent. What does “mass balance” actually mean? What are atmospheric rivers, and what part do they play in extreme events? And does this recent ice gain signal hope for the future – or is it just a brief pause in Antarctica’s contribution to rising seas?

This article is a quick summary of the full discussion on the Beyond the Ice podcast. Listen to the whole episode here:

How much ice is there in Antarctica?

Antarctica is a storage zone for around 60% of the world’s fresh water – sitting as ice sheets above the bedrock. The Antarctic ice sheet is the largest single mass of ice on Earth, and in places it is kilometres thick.

Crucially: this ice isn’t static. Antarctica is a dynamic system with inputs and outputs – for instance, the calving of icebergs is a normal part of the cycle of an ice sheet. Dr Michelle Maclennan explains:

“The output snow accumulates on the surface. It’s compacted or hardens into ice, then that ice flows outward, and flows into the ocean. And so that’s our output. But every year we’re also getting a huge amount of snow as input, which is bringing water back to the ice sheet.”

At a data level, scientists use the concept of ‘mass balance’ to describe how Antarctica is changing.

“What it means is that we’re looking at how much ice is stored in Antarctica and how that changes over time. So ,the word mass refers to essentially the weight of the ice. And when we think about how that mass is changing over time: the ice sheet can gain mass or gain weight, or it can also lose it over time.”

So when they talk about how Antarctica is changing, scientists will often talk about a negative mass balance. This means that the Antarctic Ice Sheet is losing more ice mass than it is gaining. At a continental scale, a small imbalance can have a big impact for the rest of the world:

“When Antarctica loses weight, it mostly means that the ice is flowing from the continent – from being stored on the rock – to being in the ocean. And that contributes to sea level rise.”

“Even though we’re talking about billions of metric tons of ice or water being lost to the ocean or gained, what’s actually happening is the result of quite a small imbalance.”

Measuring a continent-sized ice sheet

Antarctica is vast – larger than Australia, Europe or the United States of America, with room to spare. So how do scientists measure ice changes across such an enormous area? The main answer for contemporary measurements is satellites. Michelle explains:

“Because Antarctica – all that ice – weighs so much, it actually exerts a bit of a gravitational pull. So that pull changes over time, and it changes in certain regions of Antarctica – we can see strong regional differences in how thick different regions of ice are.”

The 2021-2023 reversal explained

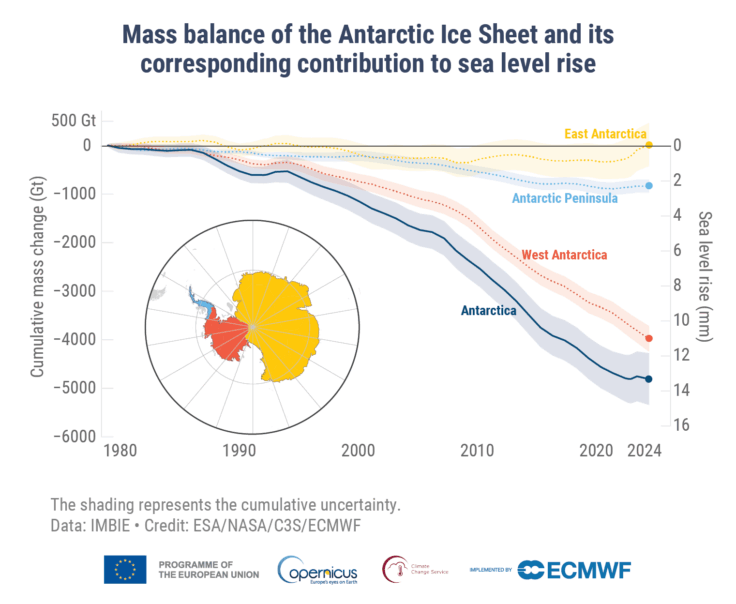

The recent study from researchers at Tongji University in China found something remarkable – after decades of mass loss since the 1970s, Antarctica briefly gained mass in the years 2021-2023.

In the years 2011 to 2020, the ice sheet was losing an average of 157 billion metric tons a year. And then in the period 2021-2023, in a period of extreme weather, the ice sheet started gaining mass. It gained about 119 million metric tons a year.

“We had a very extreme storm that hit part of Antarctica, and it brought a huge amount of snowfall to Antarctica – more than we had seen from most other extreme storms before. It was very unexpected. That caused us to see an increase in the mass of Antarctica for the first time in decades.”

The study focussed particularly on the mass gain of several large glaciers in the area of East Antarctica which was affected by the extreme snowfall. The findings highlight the complexity of Antarctica’s regional differences, with the study tracking changes across different parts of the continent over several decades.

The extreme snowfall event was caused by phenomena known as atmospheric rivers. Michelle describes them as “super charged bands of moisture in the atmosphere”, with “so much moisture concentrated in them, that it’s like having a river in the sky.” She continues:

“What happens when you increase the temperature of the air is that the air can hold exponentially more moisture or water than it could at a lower temperature.”

Climate change is expected to bring more extreme precipitation events to Antarctica:

“The cool thing about them – the coolest part – is that they can bring so much snow to Antarctica that in some years they can really help to offset some of the sea level contributions that we’re seeing.”

“But because it has this concentrated band of moisture that is transported over a long distance, these atmospheric rivers are also associated with very high temperatures. They form in Earth’s warm and wet places, so they tend to bring a lot of heat to Antarctica as well. This is normally associated with rain and melting.”

A temporary reprieve or new pattern?

In this episode, Em and Michelle discuss whether extreme events like this could be enough to offset predictions for rapid ice loss in Antarctica in the future. Michelle is clear about the broader trajectory:

“It’s most likely a short term signal. I think it’s very clear from a lot of the studies that have been done – a lot of the fieldwork people here at BAS and at other institutes have done – that we’re going to see this long term trend of of more and more ice being lost.”

Future storms could carry even more snow, but the fundamental drivers of ice loss – including warm ocean water melting glaciers from below – continue to intensify. Moreover, if the extreme precipitation falls as rain instead of snow, this is rapidly damaging to ice sheets.

Michelle recently published research in which she ran 40 simulations from a high-resolution climate model to assess the occurrence and impacts of future atmospheric rivers up to the end of the 21st century under moderate warming. She found that there would be an increasing number of extreme events, but that their impacts would seemingly be broadly comparable to what we see today – a mix of extreme snowfall, and extreme melt-inducing precipitation.

Moreover, data presented by ESA and NASA via the Copernicus programme demonstrates how small the reversal in 2021-2023 was amid the scale of long term trends across Antarctica:

Dr Michelle Maclennan is a climate scientist at British Antarctic Survey. She uses models to identify extreme weather events called atmospheric rivers, and quantify their past and future impacts on the surface of the Antarctic ice sheet.